As it glints in the afternoon sunlight, Newark, New Jersey’s Passaic River looks peaceful. But a plaque along the boardwalk has a warning for visitors. “The river remains full of life,” it reads. “Try to spot these creatures, but until the pollution is removed from the river, be careful NEVER to catch or eat any of them.”

There’s been an advisory against eating lower Passaic fish since 1983, when the EPA found they were contaminated with dioxin—chemical waste from local factories, including one that produced Agent Orange, an herbicide the U.S. military used to devastating effect in the Vietnam War. Despite health risks ranging from cancer to developmental issues, people still catch and eat fish from the lower Passaic River.

Researchers don’t know precisely how many people consume fish from the lower Passaic. Elias Rodriguez, an Environmental Protection Agency Public Information Officer, says the EPA hasn’t seen evidence of widespread fishing. According to preliminary results of an ongoing study conducted by the NYU School of Public Health’s Zelikoff Lab, those who do fish the Passaic—including several homeless people who use it as a regular food source—are often food insecure and looking to supplement their diet. Research has shown that low-income anglers are more likely to consume their catches, and Latino anglers are less likely to be informed of the health risk.

Amy Rowe, County Agent at the Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Essex County, says that the vulnerability of populations who fish in the Passaic makes the problem particularly difficult to tackle. But in 2015, Rowe and her team implemented a novel solution: a fish swap.

At the time, Rowe was co-director of the Rutgers VETS program, which trained unemployed New Jersey veterans in aquaculture and hydroponics, including fish farming. The fish grown through the program, and the communities’ need for affordable protein, seemed like a perfect match. So on Saturdays throughout the summer, Passaic anglers were encouraged to bring their catch to a parking lot by the Nutley boat launch in Lyndhurst, New Jersey. There, they could exchange fish, pound for pound, for tilapia raised by the VETS program’s trainees. Benefitting both veterans and food-insecure locals, the swap seemed like a no-brainer.

“It makes so much sense,” says Rodney Spencer, a VETS program graduate and Newark native who staffed the fish exchange.

But there was a catch. The fish swap was proposed and funded by the Cooperating Parties Group, a coalition of the same companies—including Pfizer, Rubbermaid, and Tiffany and Co.—that had polluted the Passaic River. At the same time the CPG was funding the fish exchange, they were locked in a legal battle with the EPA over the river’s cleanup. While the EPA demanded that the polluters fund a full dredging of the silty bottom of the lower eight miles of the Passaic, the CPG wanted to implement a less-expensive “hotspot” option.

The CPG claimed the fish exchange was a way to reduce harm while the lengthy cleanup got underway. “We are trying to reduce risks to the most vulnerable in our community,” Jonathan Jaffe, the CPG’s spokesperson, told NPR in 2016. Jaffe didn’t respond to multiple interview requests for this article.

Community advocates—and the EPA—disagreed. “The fish swap program was a complete deflection from the issue at hand,” says Ana Baptisa, an environmental science professor and trustee of the Ironbound Community Corporation, who co-chairs the EPA’s Lower Passaic River Community Advisory Group. When polluters first proposed the program in 2013, environmental groups labelled it “ridiculous,” and the EPA said the companies were “panicked and scrambling” to avoid paying for a full cleanup.

But for Rowe, the fish exchange was an opportunity to support the VETS program while mitigating community health risk. “We did try to work with the community,” says Rowe, who advertised the exchange extensively and gave presentations to community groups. Yet the staff continued to face heavy criticism for working with the polluters. “We were accused of taking their dirty money,” she says.

There were other roadblocks. In 2015, the greenhouse-raised fish weren’t mature enough to swap, so the Rutgers team had to exchange fishermen’s catches for frozen Costco tilapia.

There was a more fundamental problem: The fish exchange didn’t actually swap many fish. Staff scoured the Passaic’s banks for anglers. “We tried all hours of the day, all days of the week, all fishing seasons, we tried weekdays, we tried lunchtimes, we tried weekends,” Rowe says. But in the entire 2015 season, the program exchanged only 157 fish from three fishermen.

Rowe doesn’t know whether this is because there were few people fishing, or because those who did fish felt uncomfortable accessing the program. Anglers seemed reluctant to even talk to staff, let alone avail of the swap. Considering they were mostly immigrants, potentially undocumented, in a climate of increasing vulnerability, Rowe says their hesitance to approach clipboard-wielding researchers made sense. Spencer says shame may have also played a part. “People were embarrassed to have people know they were getting their only protein substance from a polluted river,” he says.

Rowe does fondly recall the enthusiasm of one father-son pair—the son translating for the Spanish-speaking father—who swapped over 80 eels in the 2015 season. Yet Spencer wonders whether they were actually bringing fish caught by others, who were too anxious or ashamed to come themselves. “You don’t want to pry too much,” he says. “You didn’t want to scare them off.”

When the fish swap ran again in summer 2016, not a single angler showed up. With funding drying up, both the fish exchange and VETS program ended shortly afterward.

Spencer says that afterwards, he and other veterans were left wondering whether the program had been a PR stunt for the polluters. “It started to seem like we were kind of bamboozled,” Spencer says.

To understand why a seemingly well-meaning fish swap could prompt such strong distrust, you have to look to the history of Newark—and the reason why, more than three decades since the EPA discovered dioxin in the Passaic, the dream of edible local fish remains distant.

Walk north from Newark’s Riverside Park—past fragrant Portuguese bakeries and through the rubble under the railroad bridge—and the Passaic is less scenic. Near a train station, an acid-orange sign warns visitors not to boat, swim, or fish in the water due to sewage overflows. North of the railway station, toppled benches ring a sign declaring “Newark’s Riverfront”; the text is too weather-worn to read. On the bank below, residents have erected tarp shanties among half-buried wire shopping carts. They have a front-row view of condos springing up among old factories on the opposite bank.

Today, Newark bears the scars of half a century of disinvestment. But in the 19th century, New Jersey’s cities were booming. Powered by the Passaic and just a stone’s throw from New York City’s rich ports and waves of immigrant labor, Newark’s factories helped drive America’s Industrial Revolution. But by the mid-20th century, industry slowed. During the white flight of the 1950s and 60s, prosperous families left Newark, taking capital with them. Today, the city is majority black and Latino—50% and 36%, as of 2018—and disproportionately poor: 28.3% of Newark residents live in poverty.

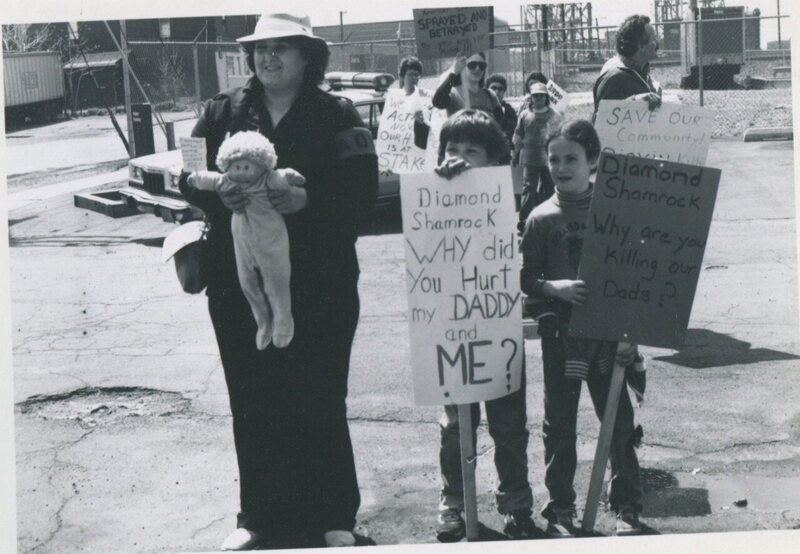

Companies took jobs away, but left pollution behind. Between 1951 and 1969, the Diamond Alkali factory in Newark produced Agent Orange. Factory workers were found to have elevated levels of the chemical, which can increase risk of immune disease and cancer. In 1983, dioxin was discovered in the surrounding community, and a year later the old Diamond Alkali factory became a Superfund site. Local residents staged protests upon the discovery of the contamination, and community groups have been pushing the EPA and corporations for a full-fledged cleanup ever since.

For Baptista, this persistent pollution is part of the broader injustice inflicted on the region’s low-income communities of color. “This really is environmental racism,” she says.

In this context, it’s easy to understand why locals would be cynical of the Cooperating Parties Group, and even of the Rutgers program. Spencer says when he entered the VETs program in 2014, he was unemployed, with three children and an ill parent to support. “I didn’t know which way I was going,” he says. He took to horticulture quickly; it gave him income and purpose. “It had me thinking like a plant. Like the growth of a plant,” he says.

But five years later, he’s still working to piece together enough agricultural consulting work to support his family. He wishes Rutgers and the city had invested more in helping veterans find sustainable employment and in growing Newark’s fledgling horticulture industry. While he’s determined to succeed, a lifetime of witnessing failed development efforts sometimes leaves him feeling cynical. Some of these failures have garnered national attention, like Mark Zuckerberg’s $100 million donation to Newark Public Schools—an effort widely criticized as having ignored parents and teachers while failing to make an impact.

Meanwhile, pollution continues to plague Newark. On a recent Tuesday in March, across from the New Jersey Performing Arts Center where Mayor Ras Baraka is about to give his annual State of the City address, a dozen or so protestors chant “Clean water for Newark!” Levels of lead in Newark’s drinking water are worse than those in Flint, Michigan, the protestors, from the Newark Water Coalition, say: as high as 47.5 parts per billion. Just as with dioxin decades ago, organizer Anthony Diaz says, “Everybody wants to cover it up.”

In March 2016, the EPA issued a Record of Decision detailing a $1.38 billion cleanup plan for the lower eight miles of the Passaic River, listing more than 100 companies that would be responsible for funding it. The plan, which is currently in the design phase, includes dredging 3.5 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment and capping the riverbed. The EPA estimates it will take about a decade. It will take even longer for the fish to be safe to eat.

Despite it all, Baptista remains optimistic. “In the next generation, can we get this river back to a state where we can actually fish?” she asks. “Don’t give up on it.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.